Other Programming Languages

To truly master a programming language, merely focusing intensely on that single language is often not enough. Thinking within the same environment can lead to a narrow perspective, and looking at problems from a different angle might open up a whole new vista. It was through exploring other languages that I began to appreciate some of the sophisticated designs in LabVIEW, as well as to reconsider some of its shortcomings that I had previously overlooked. In this book, while the main focus is on LabVIEW, I frequently compare it with other programming languages like C/C++, aiming to provide readers with a more profound understanding of the subject matter.

This section, although part of a book about LabVIEW, does not spotlight LabVIEW exclusively. Instead, we'll take a cursory look at some other programming languages, examining how they differ from LabVIEW and what their individual strengths and weaknesses are. Given the vast number of programming languages, I can only select a few particularly notable ones for brief analysis.

Why Are There So Many Programming Languages?

It's a daunting task to count the exact number of programming languages in existence. Sometimes, computer science courses even require students to create a new programming language. Considering only those languages with formal specifications and widespread usage, there are easily thousands. So, why do we need so many programming languages? Couldn't we just maintain one or a few languages to handle all programming tasks?

This scenario is nearly impossible because new tasks often require new language features, and the cost of modifying an existing programming language is prohibitively high. In most cases, it's more economical to create a new language than to overhaul an existing one. If we're faced with a new requirement that existing languages can't meet, modifying an existing language to accommodate this new need could potentially make all programs written in that language inoperable. Such a risk is unacceptable, leading to the safer route: not altering existing languages, but instead creating new ones to fulfill new demands. Therefore, the landscape of programming languages is always evolving. For instance, despite C's popularity, the need to support object-oriented programming led to the development of languages like C++ and Java.

Of course, this doesn't mean that once a programming language is designed, it remains unchangeable. In fact, any programming language with vitality is in a constant state of evolution. However, these enhancements must not interfere with any existing functionalities. For example, C++ has seen several significant updates since its inception: the introduction of templates, enhancements to the STL, and the addition of lambda functions, to name a few. The approach to programming in C++ has dramatically shifted from its early days. In my early experiences with C++ development, a significant portion of my efforts was dedicated to hunting down memory leaks and dangling pointers. Nowadays, C++ can automatically manage memory, allowing programmers to concentrate more on business logic rather than debugging bugs. Despite such substantial changes, C++ remains the same language at its core because each update has been backward compatible, ensuring that existing programs continue to compile successfully with modern C++ compilers.

There are instances, however, when language designers identify design flaws that are so critical they necessitate modifications, even if it means breaking compatibility. The transition from Python 2.0 to 3.0 is a case in point. This upgrade aimed to rectify a few design flaws, such as adding Unicode support and altering the behavior of integer division, affecting only a minority of Python code. Nonetheless, even these seemingly minor modifications required about a decade for Python to fully implement the transition.

LabVIEW releases new versions annually, primarily focusing on bug fixes or adding functionalities, thus ensuring forward compatibility without significant resistance to upgrades. However, due to LabVIEW's inability to guarantee backward compatibility — older versions of LabVIEW cannot open VIs saved with newer versions — its compatibility has been the subject of much criticism. LabVIEW faces several notorious issues that National Instruments has been reluctant to address due to concerns over compatibility. For instance, while integrating Unicode support is not inherently challenging, doing so could render existing programs reliant on non-Unicode encodings inoperable or incorrectly displayed, prompting caution in LabVIEW's encoding changes.

Despite the proliferation of new programming languages, the vast majority tend to closely resemble an existing language. Among the most popular programming languages — C++, C#, Java, PHP, and JavaScript — all are influenced by C. These languages borrowed elements such as syntax, structure, keywords, and operators directly from C. This strategy primarily aims to reduce the learning curve for new languages. For example, because Java and C++ share much of their syntax, a programmer proficient in C++ will find learning Java significantly easier. They can bypass the numerous similarities between the two languages, focusing instead on their differences, thus smoothly transitioning to programming in the new language.

The Lambda Calculus Programming Language

Let's start with a question for the reader: To what extent can a programming language be simplified?

Certain features in programming languages are clearly designed for the convenience of developers and are not strictly necessary. For example, support for object-oriented programming isn't required in an extremely minimalistic programming language. Likewise, many library functions, which exist to facilitate ease of use, could also be discarded. Is a loop structure essential? It appears that it too could be omitted, as any loop can be replaced by recursion. In the worst-case scenario, programmers could simply unroll loops into several more lines of code if they don't mind the additional hassle. But what about conditional structures? Is it possible for a programming language to function without if-else statements and still implement the needed logic? Surely basic operators like addition, subtraction, multiplication, and division are indispensable, right? Could programmers feasibly implement addition and subtraction functionalities in a language that lacks these operations?

These questions crossed my mind when I was first learning C. During one debugging session with some C code, I delved deeper and deeper into the called functions, eager to understand how a particular piece of data was being generated. Eventually, I hit a roadblock with a library function that the debugger couldn't step into. C programs often rely on many pre-compiled library functions, where programmers are familiar with the interfaces but not the implementation code. This approach is efficient but hindered my learning process. It led me to wonder: Is there a programming language out there that doesn't depend on any pre-compiled libraries, providing all functionalities directly in source code form for the programmer? This would surely simplify the learning process. Additionally, I speculated whether many of the keywords and operators also needed to be pre-compiled. What's the absolute minimal set of functionalities required by a programming language?

I found answers to these queries when I encountered a programming language known as Lambda Calculus, developed by Alonzo Church. Lambda Calculus is an exemplar of programming language minimalism. While similar minimalist languages like SKI, Iota, and Jot exist, Lambda Calculus remains the most iconic and celebrated. Just how minimalist is Lambda Calculus? Its entire syntax can be described succinctly in a few lines:

- The characters utilized in Lambda Calculus include lowercase English letters, an English period (.), parentheses, and the Greek letter lambda “λ”.

- Name: Formed by a single lowercase English letter, structured as

<name>. Examples include x, y, a, etc. - Function definition: Begins with the “λ” character, followed by a variable name, an English period, and then an expression, formatted as

λ<name>.<expression>. For instance,λx.x, which translates to the mathematical function f(x) = x. - Function application: Constructed from a function definition plus an additional expression, styled as

<function><expression>. For example,(λx.x)adenotes passing a as a parameter to the preceding function, yielding a as the result. - Name, function, and application are collectively categorized as expressions.

- Parentheses serve to dictate the order of operations. Spaces may also be incorporated to enhance readability.

This overview encapsulates the entirety of the programming language's syntax. In creating a compiler for this language, I realized that the most crucial part could be implemented in merely a dozen lines of code, making a compelling case for Lambda Calculus as one of the simplest programming languages in existence.

It's clear from observing the most basic operational rules of this programming language:

λx.xandλy.yare equivalent, which we can express asλx.x ≡ λy.y.(λx.x)asimplifies toa, or written as(λx.x)a = a.(λx.y)a = y.(λx.(λy.x))a = λy.a.

You might have noticed, this programming language lacks loops, conditional structures, and even fundamental elements like numbers, addition, and subtraction. Indeed, the only functionality a programming language must provide is function calling. With function calls alone, all other operations can be implemented. Below, we introduce how to define and implement some basic programming functionalities in Lambda Calculus:

- Implementing multi-parameter functions, a technique known as function currying, is straightforward. For example, to implement a function

f(x, y, z) = ((x, y), z), we use:λx.λy.λz.xyz. - Logical operation "true" is defined as:

TRUE ≡ λx.λy.x. Here, "true" is defined as taking two parameters and returning the first. For instance:TRUE a b ≡ (λx.λy.x) a b = (λy.a) b = a.

- Logical operation "false" is defined as:

FALSE ≡ λx.λy.y, which means it takes two parameters and returns the second. For example:FALSE a b ≡ (λx.λy.y) a b = (λy.y) b = b.

- For conditional statements like if, suppose we need to return

twhen variablebis true, andfwhenbis false. Then,IF ≡ λx.x, soIF b t f ≡ λx.x b t f. Calculating:IF TRUE t f ≡ (λx.x) (λx.λy.x) t f = (λx.λy.x) t f = tIF FALSE t f ≡ (λx.x) (λx.λy.y) t f = (λx.λy.y) t f = f

- With these foundations, defining logical operations becomes simpler. For example:

AND a b ≡ IF a b FALSEOR a b ≡ IF a TRUE bNOT a ≡ IF a FALSE TRUE

- Defining numbers:

- Focusing solely on natural numbers, as other values can be derived from them, natural numbers are defined as follows:

- 0 is a natural number.

- For any given natural number

a, there exists a distinct successora', which is also a natural number. - For any natural numbers

b,c,b = cif and only if the successor ofb= the successor ofc. - 0 is not the successor of any natural number.

- Based on this, we define natural numbers in Lambda Calculus like so:

0 ≡ λf.λx.x, noting0 ≡ FALSE.1 ≡ λf.λx.f x2 ≡ λf.λx.f (f x)3 ≡ λf.λx.f (f (f x))- ……

- Focusing solely on natural numbers, as other values can be derived from them, natural numbers are defined as follows:

- An auxiliary "successor function" is defined for easier numerical operations:

S = λn.λf.λx.f((n f) x). Calling this function yields the successor of an input parameter, for instance,S4 = 5. Trying it out:S 0 ≡ (λn.λf.λx.f((n f) x)) (λf.λx.x) = λf.λx.f(λx.x f) x) = λf.λx.f x ≡ 1

- Addition is defined as:

ADD ≡ λa λb.(a S) b. Calculating:ADD 2 3 = (λa λb.(a S) b) 2 3 = 2 S 3 ≡ (λf.λx.f (f x)) S 3 = λx. S (S x) 3 = S (S 3) = S 4 = 5

These examples showcase some of Lambda Calculus's most basic functionalities. As a Turing complete language, it's capable of far more than this; essentially, anything other programming languages can accomplish, it can too. However, leveraging it means all functionalities must be manually implemented by the programmer, which is highly inefficient. Although Lambda Calculus may not be practical as a programming language, its status as a classical educational tool has profoundly influenced the development of subsequent programming languages. Functional programming, in particular, was inspired by it, and today, Lambda functions have become a standard feature in mainstream programming languages.

The Scheme Programming Language

Scheme, a dialect of Lisp, was my first foray into the world of functional programming languages. Lisp, emerging in the 1950s, stands as humanity's second high-level programming language developed after FORTRAN. Its emblem, featuring two lambda "λ" symbols, unmistakably reflects the impact of Lambda Calculus on Lisp. Unlike the rigid standards of C++ and Java, which do not allow for arbitrary extensions, Lisp was designed to enable users not only to program within the language but also to augment the language itself with additional features. This flexibility has resulted in a plethora of Lisp dialects over the years. Some dialects were specifically tailored for individual applications, such as the renowned Emacs text editor, crafted in its bespoke Lisp variant. Today, the original Lisp language exists mostly in academic texts, with its various dialects being the primary means of utilization.

In the 1970s, MIT introduced Scheme, a pivotal branch of Lisp. Embracing a minimalist approach, Scheme pared down the core components of Lisp, symbolically reducing Lisp's two "λ" characters to a singular "λ". Scheme quickly became the instructional language of choice for computer science courses in numerous universities, including MIT. Scheme itself is not a single language but a family of languages, each adhering to a set of basic standards that define them as Scheme. During my studies, I engaged with a dialect known as Racket, though it's common practice to refer to the collective languages under the umbrella of Scheme.

Transitioning to functional programming, with its distinct philosophy from the procedural and object-oriented paradigms I was accustomed to, presented a learning curve as steep as my initial encounter with LabVIEW. True to its name, functional programming elevates functions to paramount importance, equating them with fundamental types like integers and strings. In this paradigm, functions often pass other functions as parameters, and a function's return value can itself be another function.

A comprehensive explanation of Scheme programming would necessitate an entire book. Here, I can only touch upon some of Scheme's most elementary features. Let's illustrate with the quintessential "Hello World" program. In Scheme, the code to display "Hello, World!" is as follows: (display "Hello, World!")

In this example, display functions as a means to print text on the screen, with the following string serving as its argument. In Scheme, both data (such as lists) and program structures (including functions and conditional statements) must be wrapped in parentheses, making these surrounding parentheses essential.

Looking at this single line, the difference from the common procedural programming languages doesn't seem too vast. The use of operators shows a slight variation: in Scheme expressions, operators are treated as ordinary functions, with the function name preceding its parameters. Thus, to calculate "2+3", you would write: (+ 2 3).

A more significant departure is observed in the handling of functions. Firstly, functions can be anonymous, similar to other data types. For instance, 2 is an unnamed piece of data; (lambda (x) (* x x)) represents an unnamed (anonymous) function. The lambda keyword signifies the start of a function definition, immediately followed by the function's parameters—this function takes a single parameter, x, and its body calculates the square of x.

For convenience, functions can also be named. In Scheme, the define keyword assigns names to both data and functions. For example, (define n 2) names a piece of data “n” with the value 2; (define square (lambda (x) (* x x))) names a function “square”. When defining functions, you can omit the lambda keyword for brevity, as seen in the alternative function definition (define (square x) (* x x)).

Let's say we have a group of squares with sides measuring 2, 3, 4, and 5, respectively. We can compile these measurements into a list, utilizing the list function in Scheme to create one: (list 2 3 4 5). We can then employ the map function to calculate the area of each square. The map function requires two arguments: the second is an array indicating the data set to process; the first is a function specifying the processing method for each data item. By leveraging the previously defined square function to calculate square areas, we write: (map square (list 2 3 4 5)), yielding the result: (list 4 9 16 25). Here, the square function is passed as a parameter to the map function.

Anonymous functions can serve as parameters too. For instance, to calculate the perimeter of each square, one might write: (map (lambda (x) (* x 4)) (list 2 3 4 5)), which produces the result (list 8 12 16 20).

The examples provided illustrate how the same map function can be employed to calculate not only the area of a group of squares but also their perimeters or other data points. In object-oriented programming paradigms, this kind of functionality, where calling the same method performs different operations, is typically achieved through polymorphism or dynamic binding. Conversely, in functional programming paradigms, this flexibility is realized by passing functions as arguments.

The concept of returning a function as a result might initially seem more complex than passing one as an argument. Consider the following line of code: (define (call-twice f) (lambda (x) (f (f x)))). This code defines a function named call-twice with a single parameter, f, which interestingly returns not data but another function: (lambda (x) (f (f x))). This returned function can also accept a parameter, subsequently applying the function f twice in a nested call. Essentially, call-twice accepts another function as its input and yields a new function, whose function is to perform a nested invocation of the input function twice.

For example, passing the square function we defined earlier to call-twice generates a new function that calculates the square of a square. For instance, the execution of ((call-twice square) 3) results in raising 3 to the fourth power, yielding 81. If the execution is ((call-twice (lambda (x) (* x 4))) 3), the outcome is 3*4*4 = 48. You might want to mentally work through the result of the following program: (map (call-twice square) (list 2 3 4 5)).

Lambda functions are now supported by many mainstream programming languages, with their application similar to functions in Scheme. If you have encountered them in other languages, you'll find the examples mentioned above more accessible.

My most significant insight from studying Scheme was gaining a complete understanding of recursion. Scheme lacks loops, necessitating the use of recursion for all iterative processes. This contrasts sharply with early versions of LabVIEW, which did not support recursion, requiring all recursive logic to be converted into loops. The principles of recursion can be somewhat complex, such as adopting different recursive strategies for merging a list from the beginning versus from the end.

At present, LabVIEW does not embrace functional programming. In LabVIEW, one can pass a pre-written VI as an argument through dynamic VI calls. However, LabVIEW falls short in offering a straightforward and efficient method to dynamically assemble anonymous VIs, then use them as return values or pass them to other VIs.

The Scratch Programming Language

It was in the early 2000s when I watched a lecture demonstrating a special version of LabVIEW designed specifically for children's education and for use with LEGO toys. Graphical programming, as it turns out, is more attractive to young children than text-based coding, which indeed pointed to a promising direction for LabVIEW. Unfortunately, LabVIEW was a pioneer that somehow missed the mark. Today, when mentioning graphical programming languages for children's education or toys, most people immediately think of Scratch or its various derivatives.

Scratch, which only came into existence in 2003, quickly overshadowed LabVIEW to take over the children's education sector. It must possess some unique advantages that LabVIEW couldn't compete with. Here are a few critical ones I've identified:

Open Source: Scratch was developed by MIT and embraced an open-source model right from the start. For a children's programming language, being able to control various toys is crucial. Conversely, a language that toy manufacturers can easily adopt is more likely to spread. Integrating their products with LabVIEW or even releasing a customized version involves significant costs. Even in industries where LabVIEW is dominant, such as test and measurement, its use is mainly with NI's own hardware, with very few third-party vendors integrating seamlessly. Given the lower profit margins in the toy industry, manufacturers naturally lean towards more cost-effective solutions. Being open-source, toy manufacturers can freely explore and modify Scratch's source code, enabling them to develop compatible hardware interfaces or even tailor Scratch to fit their products. Today, in addition to international companies like LEGO, many Chinese manufacturers also pair their toys with Scratch, including toys from Xiaomi. Beyond education and toys, there are numerous Scratch derivatives combined with industrial hardware.

Simpler Syntax: Scratch significantly diverges from LabVIEW in terms of syntax, concealing more of the programming details to facilitate easier learning for beginners. Although LabVIEW also markets itself as beginner-friendly, Scratch is the true epitome of user-friendly programming.

Mainstream Technology Adoption: Scratch employs HTML5 standards and uses JavaScript for development, contrasting with LabVIEW's tendency to lean on mature, corporately endorsed technologies due to its industrial background. For instance, even as HTML5 was recognized as the emerging trend, LabVIEW opted for Microsoft's SilverLight as its development platform for web versions. Microsoft's subsequent discontinuation of SilverLight undoubtedly had implications for LabVIEW's development and dissemination.

Scratch is accessible via a web interface, eliminating the need for software installation on computers. Users can simply navigate to its official webpage in a browser to begin programming:

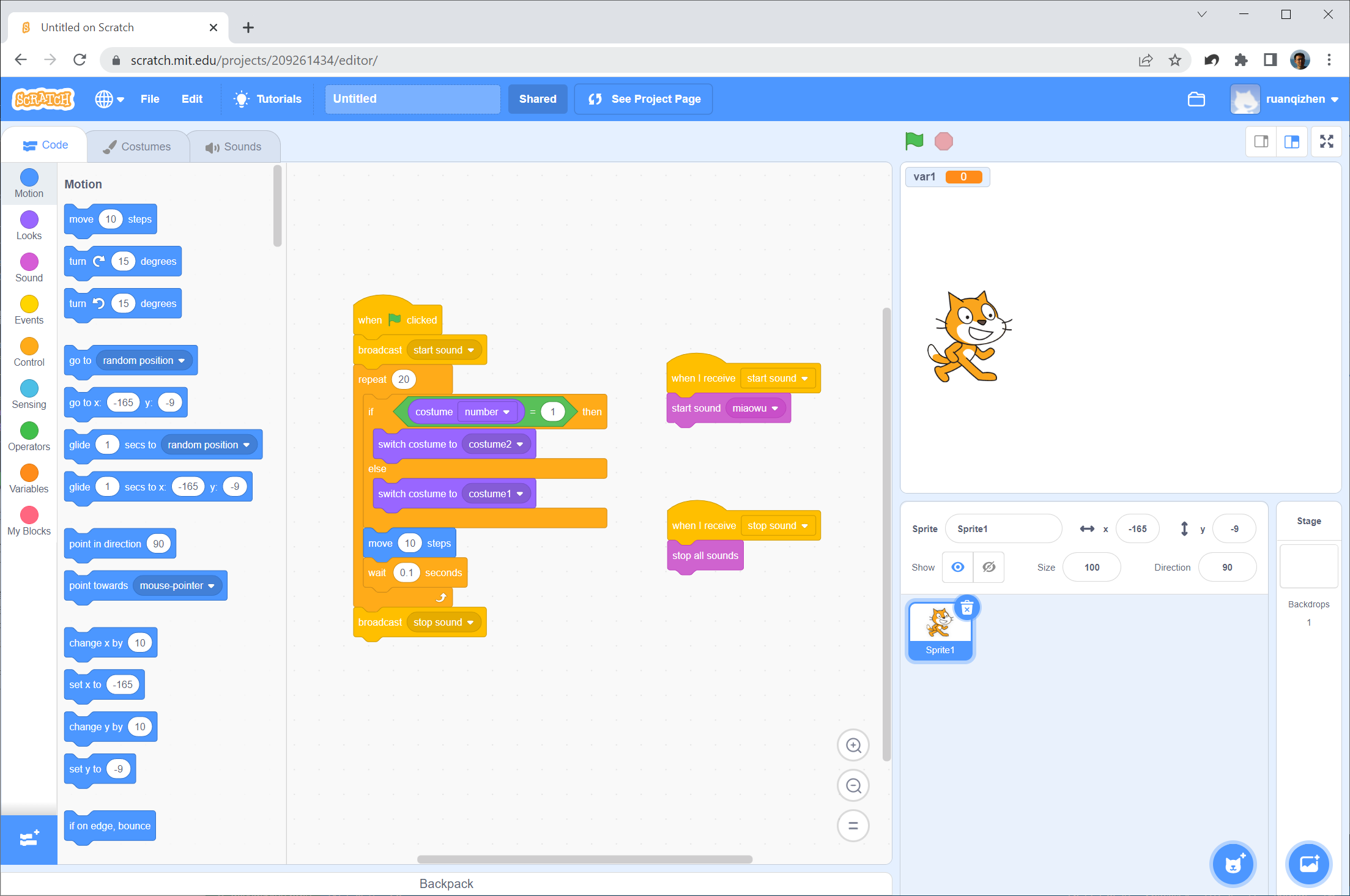

The Scratch programming interface is divided into three main sections: left, center, and right. The left section displays the available programming blocks, similar to LabVIEW's function palette. The center is dedicated to coding, akin to LabVIEW's block diagram. The upper-right section is reserved for previewing the execution results of the program, mirroring LabVIEW's front panel.

Scratch, as a web-based programming language, has its limitations. Users can draw backgrounds or cartoon characters within the interface and even record sounds. The program is capable of responding to user interactions on the interface, controlling the movements of cartoon characters, and playing sounds, among other functions. The fundamental components of Scratch programs are colorful blocks, often referred to as "blocks" or "sprites." The programming approach in Scratch resembles building with blocks; stacking different blocks in a sequence to form a program. In the example program shown, the blocks are arranged into three groups, which run in parallel because they are not connected. Each block group begins with an event trigger. The large group on the left is the main program, which starts running upon a user clicking the green flag event, emitting some events (via the broadcast block) during its execution. The other two block groups are activated by these messages to either play or stop sounds. Besides broadcasting messages, the main program also executes a loop, repeat 20, within which it calls the move function to advance a little fox (illustrated in “costume”) across the screen. The smaller block group on the right side enables the fox to make a "meow" sound simultaneously.

This program illustrates some stark differences between Scratch and LabVIEW:

Graphical Interface: Scratch's graphical interface is not as exhaustive as LabVIEW's. It also draws from text-based programming languages, depending more on text for programming. For instance, many blocks in Scratch, despite having identical shapes and colors, must be differentiated by the text on them. To exaggerate, if you were to add colorful background strips to each line of a Basic language code, it might resemble a Scratch program. LabVIEW encourages assigning meaningful icons to each sub-VI rather than relying on VI names for differentiation. This practice makes LabVIEW code visually appealing, although some programmers prefer focusing on improving program logic rather than on aesthetic aspects.

Node Appearance: LabVIEW showcases a diverse range of nodes, each with its unique appearance. Sub-VIs resemble small squares, while structures like for loops appear as frames on a section of the block diagram. In Scratch, all blocks look somewhat similar, using colors to distinguish between major functional categories, such as light yellow for event handling, dark yellow for program flow control, magenta for sound control, and blue for motion control. LabVIEW programs exhibit greater variety, with novice and expert users likely producing programs with different styles. Scratch programs tend to have a more monotonous style, regardless of functionality, appearing as stacks of blocks.

Data Flow: LabVIEW uses wires for data transmission and to dictate the program's execution order. Scratch, lacking wires, utilizes global variables for data transfer. Blocks connected together execute sequentially from top to bottom; those not connected can execute in parallel.

Data Type Differentiation: LabVIEW distinguishes data types through color coding. Conversely, Scratch uses different shapes to denote different data types, such as rounded rectangles for numeric data and pointed rectangles for boolean data. This approach ensures data type safety, ensuring, for example, that only boolean data (akin to a function with a boolean input) can fit into a block designed for boolean inputs.

Hardware Control: LabVIEW's goal is to control all hardware devices with one language. Scratch has led to numerous derivative languages tailored to specific hardware types. These derivatives primarily incorporate abilities to receive hardware-generated events, read data from hardware sensors, and control hardware movements (like cars or robots).

The Python Programming Language

The programming languages we've discussed each possess their unique characteristics. However, sometimes, a very distinctive personality might not align with the broader audience's preferences. In fact, the most popular languages tend to be those that strike a balance: they may not have unparalleled features, but they also lack significant drawbacks. Python is one such language. Providing a comprehensive summary of Python in just a few sentences is quite a challenge, which is why I authored a book dedicated to thoroughly exploring the Python programming language: https://py.qizhen.xyz/.