String and Path

String Data Type

In LabVIEW, the storage format for strings is somewhat similar to that in the C language, with both utilizing a numeric array represented as U8 (unsigned 8-bit integers). However, a key difference lies in how the end of a string is marked. In C, a string is terminated with the \0 character, while in LabVIEW, strings include length information, eliminating the need for a special terminator.

Given that strings are stored in memory similarly to U8 arrays, converting between these two data types is logical and meaningful. When a U8 array is converted into a string, each element represents the ASCII code of the corresponding character in the string. Viewing a string in hexadecimal format also reveals the ASCII codes of its characters. LabVIEW offers dedicated functions for this conversion: "String to Byte Array Conversion " and "Byte Array to String Conversion". Therefore, there's no need to resort to forced type conversion. The two methods shown below achieve the same result:

As of the current version (2023), LabVIEW does not support Unicode under the Windows operating system. For more information on this limitation, please refer to the section LabVIEW's unicode problem. When using non-English characters (those outside the ASCII range) in LabVIEW, be aware that switching operating systems (e.g., from a Chinese to a French system, or from Windows to Linux) may cause these strings to display incorrectly, potentially resulting in garbled text.

String Control

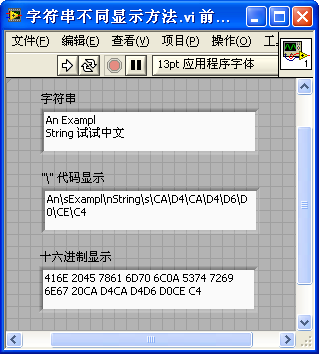

LabVIEW's string control offers several versatile display methods beyond the standard display. These include "'\' Code Display", "Hexadecimal Display", and "Password Display" modes:

In strings, certain characters like carriage returns and line feeds have special meanings or are not directly displayable. The "'\' Code Display" mode is useful in these situations, as it utilizes \ escape codes to represent such characters. This approach is familiar to those who have experience with text programming languages, like C, which uses similar escape characters in strings. In LabVIEW, common escape characters include \n for a newline, \r for a carriage return, \t for a tab, \s for space, and \\ for the backslash character itself.

When LabVIEW interacts with devices or reads and writes certain files, string data types are often used. However, this data may not always be text but could represent numerical information. In such cases, displaying this data as text might result in meaningless characters or symbols, akin to viewing an EXE file in Notepad. The "Hexadecimal Display" mode is particularly useful here, allowing for the numerical representation of such data.

The "Password Display" mode, as the name implies, masks all characters with an asterisk *, making it suitable for password entry fields.

The combo box control also utilizes the string data type. It can be used to restrict user selections to predefined string options. The relationship between the combo box and string control is analogous to that between the Dropdown List Control and a standard numeric control. These display options enhance the versatility of string controls in LabVIEW, catering to a range of applications and user interface requirements.

Converting between Numbers, Time and Strings

Basic Conversion Functions

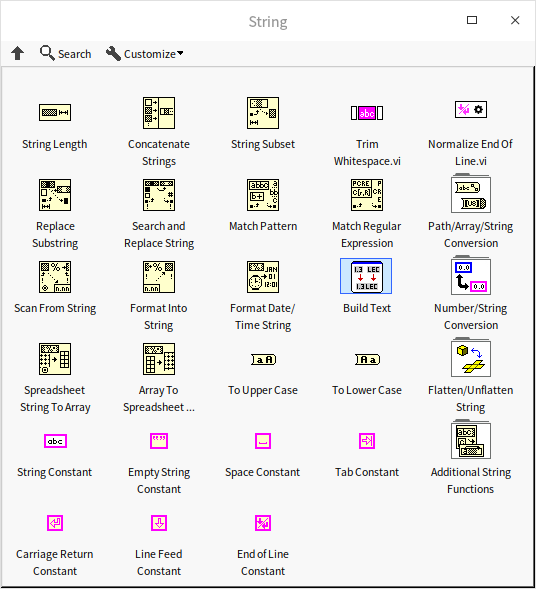

The primary functions related to string manipulation in LabVIEW are located under the "Programming -> String" function palette:

Many string functions, such as calculating string length or merging strings, are quite intuitive and can be used effectively without much prior knowledge. Here, we'll focus on some slightly more complex yet frequently used functions, particularly those involving conversions between numbers and strings.

Conversion between numbers and strings is a common requirement. Numerical data is essential for calculations, while string representation is often needed for display purposes (e.g., embedding data values in explanatory text) or when storing data in a file. LabVIEW offers two sets of functions for converting between numbers and strings, with the more user-friendly set located under "Programming -> String -> String/Number Conversion". These functions allow users to select the appropriate conversion based on data radix, notation, and other criteria.

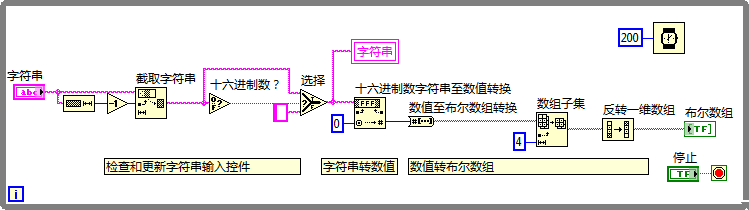

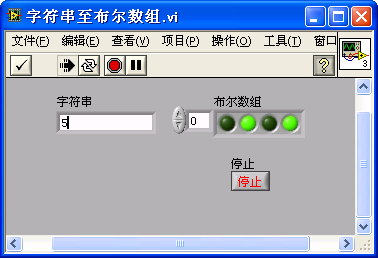

Consider a specific example program: String conversion to boolean array. This program takes a hexadecimal character as input and outputs a 4-bit Boolean array corresponding to that character.

The program can be broken down into several components: the first part restricts the input string to characters 0–9 and A–F; the second part converts the character into U8 data; and the final part displays the lower four bits of the U8 data as a Boolean array. While these components could be separated into individual subVIs, for demonstration purposes, we present all the code on a single block diagram:

A key point in this program is selecting the appropriate data type conversion function. The program's output is shown below:

String Formatting

The "Programming -> String" function palette includes two powerful conversion functions: "Formatted Into String" and "Scan From String". These functions correspond to the sprintf() and sscanf() functions in the C language. While they can handle multiple data types simultaneously and offer richer formatting options compared to the basic conversion functions, using them effectively requires familiarity with format string syntax, which LabVIEW borrows from C.

"Formatted Into String" allows input data to be converted into a string according to a user-specified format. This is achieved using a format string, which may include both non-format and format segments. Non-format segments are output as is, while format segments start with % and are followed by characters that define the type, form, length, decimal places, and other attributes of the output data. The general form of a format string is %[minimum output width][.precision][length]type. Commonly used format specifiers in LabVIEW include:

%d: Converts a signed decimal integer to a string. For instance,%4dpads the output with spaces on the left if the number has fewer than 4 digits and displays the actual number of digits if greater.%u: Converts an unsigned decimal integer to a string.%f: Converts a decimal number to a string using decimal notation. For example,%6.2fensures the string has at least 6 characters, including 2 decimal places, padding with spaces if necessary.%e: Converts a decimal number to a string using scientific notation.%g: Automatically selects between%for%eformat based on the data size.%s: Converts an input string to formatted output, with the option to set width.%%: Outputs a percent character%.

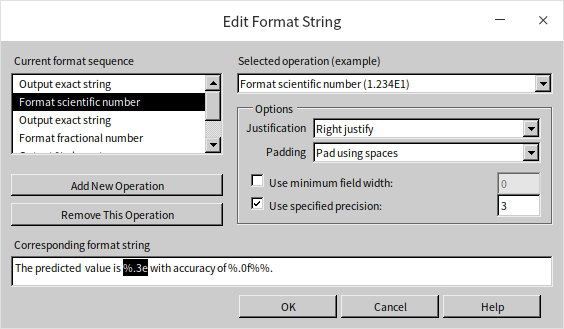

If you're unsure about format symbols, there's a helpful tool at your disposal. LabVIEW provides an "Edit Format String" dialog box to assist users in configuring the appropriate format symbols. Right-click on the "Formatted Into String" or "Scan From String" function and select "Edit Format String" to access this feature. You can then choose the required data type from the "Select Operation" dropdown menu to configure it:

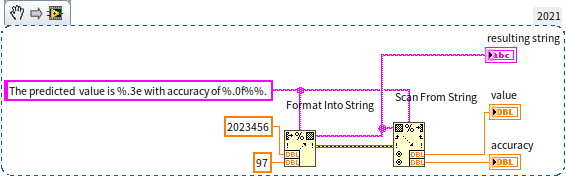

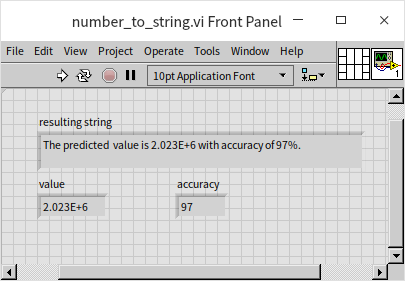

"Scan From String" utilizes the same formatted string to extract data from an input string. In the following example, a formatted string is used to insert two input data into a string, and the same formatted string is then used to read the data from this generated string:

Program running result:

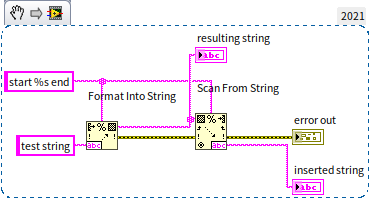

However, be cautious when extracting string type data using the "Scan From String" function. This function can sometimes be less intuitive, as demonstrated by the runtime error in the following program:

This error occurs because the function struggles to match %s when all input data are strings. This issue can be resolved using regular expressions, which will be introduced later.

Let's look at another example program: String Formula Evaluation. This program requires inputting a string representing a simple mathematical formula (e.g., sin(pi(1/2)) + 3*5 - 2) and outputs the real number value of this formula after calculation.

At first glance, this task seems to involve converting strings to numerical values, as well as using formula Express VIs and formula nodes mentioned in the Numeric and Boolean section. However, these methods alone are insufficient for this complex problem, which requires converting numbers in the string into numeric data and transforming the operators into corresponding calculations. Moreover, formula Express VIs and formula nodes can only set a fixed formula during program editing and don't allow changing the formula after the program runs.

Before starting to write a program, it's wise to check if existing LabVIEW functions or VIs can fulfill or partially fulfill the task, avoiding redundant work. A good place to start searching is the "Math -> Script & Formula" function palette. By browsing through the instant help window, you may find that the "Math -> Script & Formula -> 1D 2D Analysis -> String Formula Evaluation" VI aligns well with the task requirements and can be used directly:

Interested readers can explore the source code of this VI for insights. For beginners, the VI's programming might seem complex. A simplified version of this string formula evaluation function, utilizing a state machine, will be introduced in the State Machine section. This example demonstrates the power of LabVIEW's string handling capabilities, particularly when working with complex data and formulas.

Converting Between Time and Strings

In everyday applications, it's common to convert time data into a specific string format for display. LabVIEW's "Get Date/Time String" function is handy for this purpose, as it converts time into the system's default display format. When a more complex format is required, the "Format Date/Time String" function is the tool of choice. This function allows for a high degree of customization in how the date and time are presented.

Converting a string representation of time back into a time data type, however, is not as straightforward. This is primarily due to the variety of ways time can be represented as a string, with each format necessitating a different approach. LabVIEW does not provide a universal, simple function for this conversion. Instead, the "Scan From String" function is used. By carefully setting the format string, specific values can be extracted from the string representation and then converted into time data.

It's important to note that the format conversion characters used for time-string conversions in LabVIEW are unique extensions of the platform. These specific format characters do not have direct equivalents in the C language, which typically uses numeric data types to represent time. This distinction highlights the specialized capabilities of LabVIEW in handling and converting time data, catering to the diverse needs of time-based applications.

Regular Expressions

Introduction to Regular Expressions

In programming, a common task is searching for specific patterns within a larger text. If the objective is to locate a specific string, such as every occurrence of the word "dog" in a text, the "Search and Replace String" function in LabVIEW can be used. However, often the requirement is to find strings that fit a certain pattern rather than a fixed text. For instance, identifying all function names or variable names in a C language script involves searching for patterns rather than exact strings. Writing a complex program to perform such checks can be quite cumbersome.

LabVIEW provides a more efficient solution for these scenarios: regular expressions. A regular expression is a text pattern composed of standard characters (like letters and numbers) and special characters (known as "metacharacters"). These patterns are used to describe and identify strings that conform to specific syntactical rules. While regular expressions can be intricate, they are a powerful tool that can significantly enhance productivity once mastered. They are not only useful in programming but also in tasks like editing documents. For instance, in this book's Markdown manuscript, the image format is . To modify all image paths in the document, a regular expression that matches the pattern of the exclamation mark, followed by square brackets and then parentheses, is required to extract the content within the parentheses.

Match Pattern

LabVIEW offers two functions for string matching based on regular expressions: "Match Pattern" and "Match Regular Expression". The "Match Pattern" function is simpler and faster, while the "Match Regular Expression" function provides more powerful capabilities at the expense of speed. For straightforward tasks, such as extracting all values or content within parentheses from a text, "Match Pattern" is sufficient.

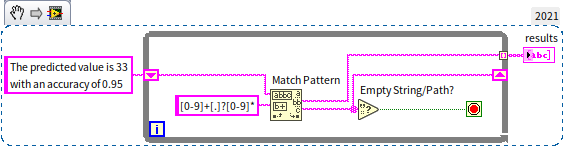

The following example demonstrates how to extract all numerical values from an input text using "Match Pattern". Since there could be multiple values, a loop is necessary. Each iteration extracts a matched value and then continues to search through the subsequent text:

The program shown above uses a regular expression to extract numerical values from a text string. The result of this program is an array: [33, 0.95]. The regular expression used here is [0-9]+[.]?[0-9]*. In this pattern:

[0-9]matches any numeric character between 0 and 9.+signifies one or more occurrences of the preceding element.[0-9]+collectively matches one or more numeric characters (i.e., an integer).[.]represents a decimal point (alternatively,\.can be used).?denotes 0 or 1 occurrence of the preceding element, making[.]?indicate an optional decimal point.*signifies 0 or more occurrences, so[0-9]*matches any number of numeric characters (i.e., the fractional part of a decimal, if present).

The "Match Pattern" function searches the input string from the beginning, matching against the regular expression. In this example, it successfully matches "33" and then "0.95" as valid numbers according to the pattern.

This regular expression is a simplified approach for matching decimal numbers and may not cover all cases. A more precise pattern might be needed for complex scenarios. Consider another example where the input is a valid VI file path in the Windows system, and the objective is to extract the file name. The program below accomplishes this:

Running result:

The regular expression used for matching the VI file name is [^\\]+\.[Vv][Ii]$. This pattern breaks down as follows:

\\matches a backslash (double backslashes are used because a single backslash is a special character in regular expressions).[^\\]matches any character that is not a backslash, which is the path separator in Windows.[^\\]+collectively matches all characters until the last backslash, essentially capturing the file name.[Vv]matches either an uppercase 'V' or a lowercase 'v'..is for the dot before the file extension.[Ii]matches either an uppercase 'I' or a lowercase 'i'.$asserts that the match must occur at the end of the input string (ensuring the pattern matches file names ending with ".vi" or ".VI", but not names like "abc.vim" or "template.vit").

Regular Expression Metacharacters

The table below lists the commonly used characters and usage in regular expressions:

| Metacharacter | Description |

|---|---|

\ | Marks the next character as special, a literal, a backward reference, or an octal escape. E.g., n matches "n", \n matches a newline; \\ matches "\"; \( matches "(". |

^ | The matched string must start from the beginning of the input string. |

$ | The matched string must end at the end of the input string. |

* | Matches the previous subexpression zero or more times. E.g., fo* can match "f" or "fo" or "foo". Equivalent to {0,}. |

+ | Matches the previous subexpression one or more times. E.g., fo+ can match "fo" or "foo" but not "f". Equivalent to {1,}. |

? | Matches the previous subexpression zero or one time. E.g., fo? can match "f" or "fo". Equivalent to {0,1}. |

{n} | n is a non-negative integer. Matches exactly n times. Only in "Match Regular Expression" function. E.g., fo{2} matches "foo" but not "f" or "fo". |

{n,} | n is a non-negative integer. Matches at least n times. Only in "Match Regular Expression" function. E.g., fo{2,} matches "foo" or "fooooooo". o{1,} is equivalent to o+; o{0,} is equivalent to o*. |

{n,m} | m and n are non-negative integers, n<=m. Matches at least n and at most m times. Only in "Match Regular Expression" function. E.g., fo{1,3} can match "fo" or "foo" or "fooo". o{0,1} is equivalent to o?". |

? (following limiters) | When ? follows limiters (*, +, {}), the match is non-greedy. E.g., for "oooo", o+? matches one "o", while o+ matches all "o". |

. | Matches any single character except newline. To include newline, use (.|\n). |

| x|y | Matches either x or y. Only in "Match Regular Expression" function. E.g., a|view matches "a" or "view"; (a|v)iew matches "aiew" or "view", equivalent to [av]iew. |

[xyz] | Matches any one character in the brackets. E.g., [abc] matches "a" or "b" or "c". |

[^xyz] | Matches any character not in the brackets. E.g., [^abc] matches "f" or "g". |

[a-z] | Matches any character in the specified range. E.g., [a-c] matches "a" or "b" or "c". |

[^a-z] | Matches any character not in the specified range. E.g., [^a-e] matches "f" or "g". |

\b | Matches a word boundary, e.g., \blab matches "lab" in "labview", but not in "collaborate". |

\cx | Matches the ASCII control character specified by x. E.g., \cJ matches a newline. |

\d | Matches a numeric character. Equivalent to [0-9]. |

\D | Matches a non-numeric character. Equivalent to [^0-9]. |

\f | Matches a form feed. Equivalent to \x0c and \cL. |

\n | Matches a newline. Equivalent to \x0a and \cJ. |

\r | Matches a carriage return. Equivalent to \x0d and \cM. |

\s | Matches any whitespace character, including space, tab, form feed, etc. Equivalent to [\f\n\r\t]. |

\S | Matches any non-whitespace character. Equivalent to [^\f\n\r\t]. |

\t | Matches a tab. Equivalent to \x09 and \cI. |

\w | Matches any word character including underscore. Equivalent to [A-Za-z0-9_]. |

\W | Matches any non-word character. Equivalent to [^A-Za-z0-9_]. |

\xn | n is a hexadecimal value, matches the ASCII character corresponding to n. E.g., \x41 matches "A". |

\n (octal) | n is an octal value, matches the ASCII character corresponding to n. E.g., \101 matches "A". |

Match Regular Expression

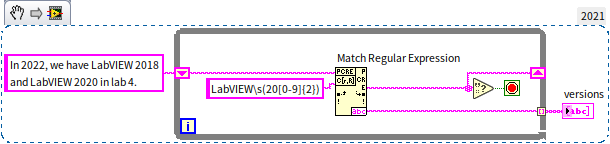

Regular expression aficionados might notice that LabVIEW's regular expression capabilities do not include lookahead matching. For instance, if we need to extract LabVIEW version numbers from a text like "In 2022, we have LabVIEW 2018 and LabVIEW 2020 in lab 4", aiming to retrieve "2018" and "2020" without including "LabVIEW", the task becomes more challenging. In environments supporting lookahead, a pattern like (?<=LabVIEW\s)20[0-9]{2} would suffice. However, LabVIEW requires a workaround using nested matching.

One approach is to first match "LabVIEW" along with the following version number using LabVIEW\s20[0-9][0-9] and then extract just the version number with 20[0-9][0-9]. LabVIEW's "Match Regular Expression" function facilitates this by allowing nested matches within parentheses, outputting sub-match results. The following program demonstrates this method to identify all LabVIEW version numbers:

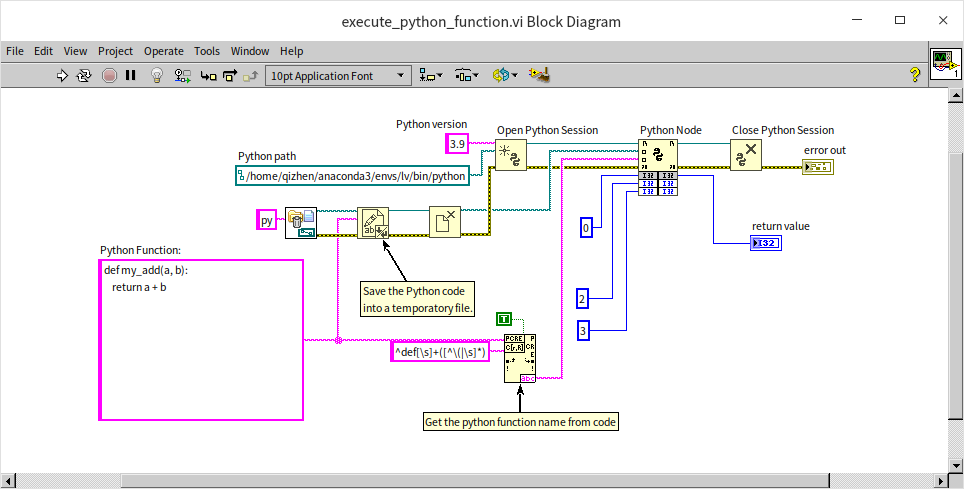

Another practical application is when interfacing with Python code. We can use regular expressions to pinpoint function names in Python scripts. Python function definitions typically start with the keyword 'def'. The following program matches lines defining functions:

The regular expression for matching function names is ^def[\s]+([^\(\s]*). Here, ^ signifies that "def" must appear at the start of a line. The content in parentheses ([^\(\s]*) captures the function name, defined as a string not containing parentheses or spaces, following "def". The "multiple?" parameter in the "Match Regular Expression" function is set to "true" to enable matching across multiple lines, accommodating function definitions that may not be at the start of the input text.

Readers can explore further with some commonly used regular expressions:

- To match an email address:

^[a-z0-9_\.-]+@[\da-z\.-]+\.[a-z\.]{2,6}$. - To match an unsigned decimal:

([1-9]\d*\.?\d*)|(0\.\d*[1-9]).

Path

Path Data

Path data is a unique type in LabVIEW, tailored to address the cross-platform challenges of path representation. In text programming languages, paths are typically represented using strings, but this approach can be problematic for cross-platform compatibility due to varying path separators in different operating systems. For example, Windows uses a backslash "\" as a path separator; Linux uses a forward slash "/"; Mac OS uses a colon ":". A string representation of a path that works for one operating system may not be universally applicable.

As a cross-platform language, LabVIEW resolves this issue by employing a specialized data type for paths. Path data in LabVIEW encompasses two components: the path type (whether it's relative or absolute) and the path data itself, which is stored as a string array. This array contains the names of each directory in the path hierarchy, from root to branch. The appropriate path separator is added for display purposes based on the operating system, ensuring that the path data remains valid across different platforms.

Relative Paths

When working with path data in LabVIEW, it's generally best to use relative paths. This practice ensures that the program remains functional even when its location changes, such as when converting it into an executable file (.exe) or transferring it to another computer.

For instance, if a program needs to access a specific file, you can place this file in the same directory as the program's main VI. The program then records the file's relative path (). Each time the program is run, it should first retrieve the main VI's current path using the "Current VI Path" constant, and then combine it with the recorded relative path to construct the full path of the data file. For example, if the main VI is

main.vi located in the C drive's root directory, its current path is C:\main.vi, and the file's path would be C:\data.txt.

All functions and constants related to path data are found under the "Programming -> File I/O" sub-panel in LabVIEW, providing a comprehensive suite of tools for efficient path management.

Path Constants

LabVIEW offers various path constants as references for using relative paths effectively. These constants are particularly useful for adapting paths dynamically based on the VI's location. For instance, in the previously discussed example, the program uses the "Current VI Path" constant to determine the location of the main VI. If the location of the main VI changes, the value of this constant changes accordingly, ensuring that the program can adapt to different file locations.

Converting Between Path and Other Data Types

Conversion functions related to paths are found under the "Programming -> File I/O-> Advanced File Functions" palette. The most commonly used functions include "Path to String Conversion" () and "String to Path Conversion" (

), which allow for seamless conversion between paths and strings.

Additionally, as path data inherently contains two pieces of information (path type and a string array of folder names), you can use "Path to String Array Conversion" () and "String Array to Path Conversion" (

) for transforming between paths and string arrays.

The "Reference Handle to Path Conversion" () function is useful for retrieving file path information from a file's reference handle. This function is applicable for converting handles output by functions in "Open/Create/Replace File" into paths, including TDMS file paths. However, it's important to note that this function is not suitable for all file types in LabVIEW, such as INI files opened by the "Open Configuration Data" VI.

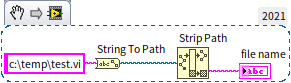

The conversion between strings and paths is operating system dependent due to different path separators used across platforms. The previous discussion on regular expressions included an example of extracting a filename from a path, like "test.vi" from c:\temp\test.vi. Under Windows, the following program can achieve this:

However, this approach may not yield correct results on a Linux system, as Linux uses "/" instead of "\" as the path separator. If your application needs to support multiple operating systems, consider using regular expressions for a more robust and universal solution to match file names.

Data Flattening

What is Data Flattening?

Data flattening, also known as data serialization, is the process of transforming structured, multi-level data into a single-level, continuous format. This transformation is essential for efficiently storing data on memory or disk devices and transmitting it over networks. Most simple data types, including numeric arrays, are inherently stored in memory in a flattened state, meaning their data occupies a contiguous block of memory.

For data types that are already stored in memory in a flattened form, the forced type conversion function can be utilized. The default target type for this function is the string type. Converting general simple data types (excluding strings and U8 arrays) to strings is effectively the same as using the "Flatten to String" function. Since these data are inherently stored in a flattened manner, converting them into strings does not alter their original data. Instead, it simply uses strings to represent the data's memory representation.

When dealing with complex data types, forcing type conversion to strings might result in some loss of data type information compared to the "Flatten to String" method. However, the actual data content remains consistent between the two approaches. For instance, when a numeric array is flattened to a string, the resulting string includes information about the array's length and its data. In contrast, forcing type conversion to a string only retains the array data information without the length detail.

Flattening to String

In LabVIEW, different data types are stored in memory in various formats. Simple data types like numbers and strings are allocated contiguous memory spaces. However, this is not the case for all data types.

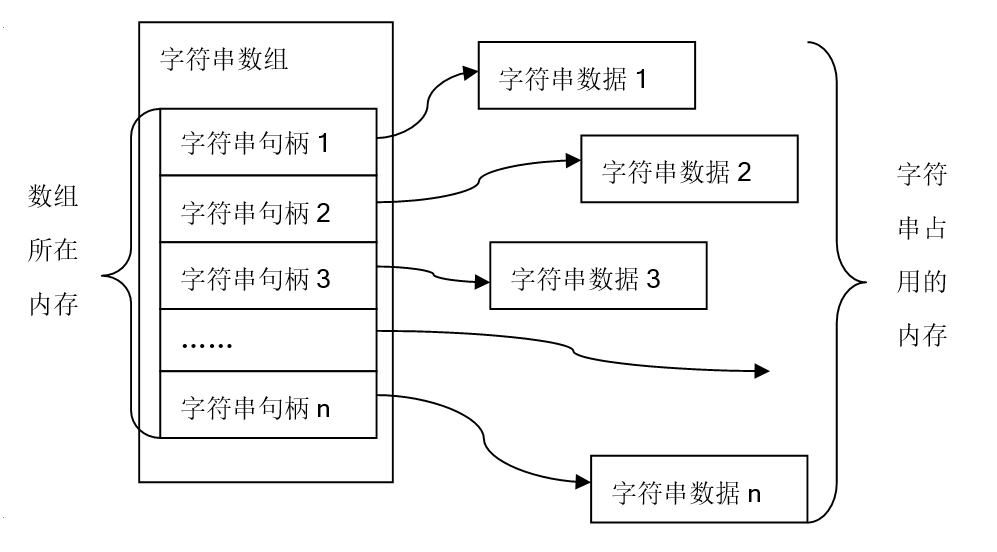

For instance, consider a string array. In memory, the array holds the handles of each element string arranged sequentially. Each handle points to a separate memory location where the actual string content is stored. This type of data structure, often referred to as a tree structure, is illustrated below:

When it's necessary to save data to a hard disk or transfer it to other computers or hardware devices (such as sending a string array to another computer via TCP/IP or transferring data to a peripheral device via a serial line), data represented by linked lists, trees, etc., must be organized into a continuous block of data. This process of converting data into a continuous and coherent format is known as "flattening". For example, flattening a string array means transforming its tree structure in memory into a continuous and linear memory block.

The "Flatten to String" function (found under "Programming -> Numeric -> Data Operation") can flatten any data type, regardless of its original format. Its output is a string that represents not a readable text, but a continuous block of memory data in string form. This string data is not meant to be interpreted literally but is used when saving data or exchanging data with other devices, programs, etc. Flattening provides a convenient way to store or transmit data.

The flattened data can be reverted back to its original data type using the "Unflatten from String" function.

Additionally, in the "Programming -> Cluster, Class & Variant -> Variant" function palette, there are similar functions for converting between variants and flattened strings. However, these functions are specifically designed for handling variant types and are not as commonly used in broader applications.

Flattening to XML

The main drawback of data flattening to a string is that the resulting information is not directly interpretable. This poses a challenge in scenarios where people need to read data files directly or monitor data content in real-time. In such cases, flattening data to XML (Extensible Markup Language) is a viable alternative. XML's hallmark is its use of tags to provide context and meaning to text data. For example, consider this XML snippet:

<data label="input" type="DBL">34.2</data>

This line of XML (for demonstration purposes and not directly generated by LabVIEW) encodes the value "34.2" within a "data" tag, indicating that it's a piece of data. XML tags are enclosed in angle brackets <>, with each tag featuring a corresponding closing tag. In this example, the data tag has two attributes: "label" and "type", each with its value, signifying the data's title ("input") and type ("DBL").

While natural language offers a multitude of ways to express data's meaning, its flexibility can be cumbersome for computer interpretation. XML provides a more standardized method for encoding data meaning with tags, facilitating consistent computer interpretation.

The "Flatten to XML" function (found under "Programming -> File I/O -> XML -> LabVIEW Mode") can transform any data type into XML text. The counterpart "Restore from XML" function enables the reversion of this process. The following figure demonstrates a program that flattens a value into XML text:

The XML output obtained from flattening the value:

LabVIEW uses simple English tags for XML, making them relatively easy to understand. In this example, the "DBL" tag wraps the entire data, indicating a double-precision real number. The "Name" tag specifies the data's name as "某数据", and the "Val" tag reveals its value of 12.3.

Due to its dual human-machine readability, XML has seen widespread use in networks, databases, and other fields. When saving data as text files or transmitting data in text form, converting data into XML format is a strategic choice.

The primary downside of XML is its inefficiency. The addition of numerous tags in XML format increases storage requirements and the computational load for parsing these tags. Therefore, applications demanding high space efficiency and performance should consider alternatives to XML format data.

Flattening to JSON

While XML is a robust and flexible format, its complexity can be a drawback for users who require only a fraction of its capabilities. Most LabVIEW users engage with XML merely to convert data into a human-readable text format. XML's extensive specifications like DTD, XSD, XPath, XSLT, among others, are often underutilized, adding unnecessary complexity and overhead. Recognizing these limitations, JavaScript developers introduced JSON (JavaScript Object Notation) in 2002, six years after XML's debut, as a simpler alternative for certain applications. Rapidly adopted into the JavaScript language standard by the European Computer Manufacturers Association (ECMA), JSON has now surpassed XML in application scope, with widespread support across various programming languages.

JSON's format is straightforward:

- Numeric data is written as plain text.

- String data is enclosed in double quotes.

- Arrays are denoted by square brackets.

- Clusters (objects in JSON terminology) are represented with curly braces.

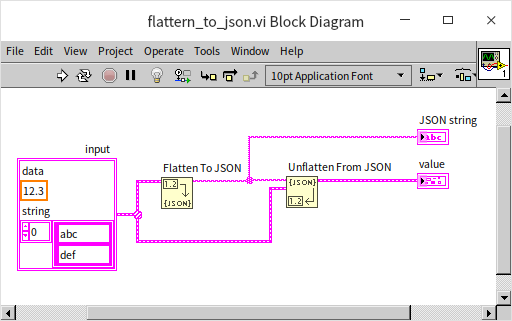

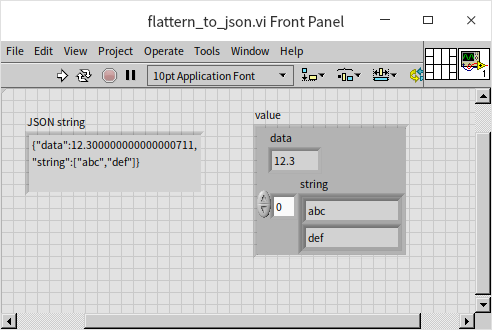

Consider this LabVIEW example demonstrating data flattening to JSON:

The program's result shows data represented in JSON format:

Given its higher efficiency compared to XML, JSON is often the preferred choice for data flattening. However, it's worth noting that LabVIEW's support for JSON may not be as comprehensive, and certain data types may not directly flatten into JSON. In such scenarios, XML remains a viable alternative.

Practice Exercise

- Consider two one-dimensional string array constants, each containing a list of student names. Write a VI to merge these names into a single array and sort them alphabetically.